A People of Many Roots

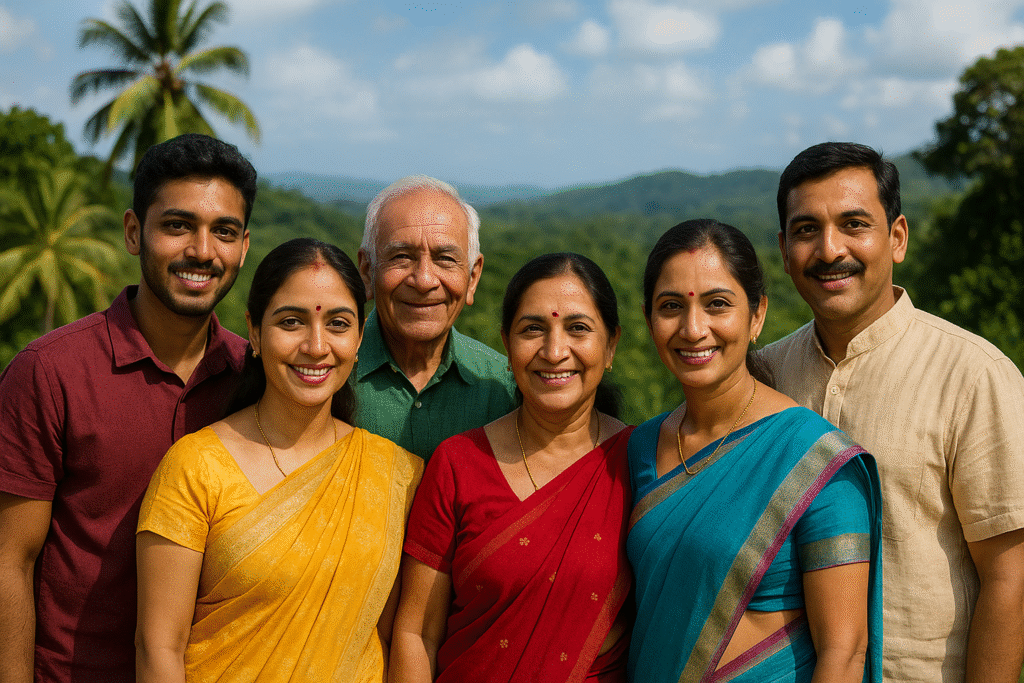

Jamaica is often praised for its national motto: Out of Many, One People. This phrase doesn’t merely echo patriotic sentiment — it encapsulates the nation’s deep and complex multicultural identity. As of 2024, Jamaica’s demographic makeup is approximately 76.3% of African descent, 15.1% Afro-European (mixed), 3.4% East Indian and Afro-East Indian, 3.2% Caucasian (White), 1.2% Chinese, and 0.8% Other. Among these groups, Indo-Jamaicans — descendants of Indian indentured labourers and later migrants — represent the largest ethnic minority in the country, critical in Jamaican culture.

Their journey is one of displacement, hardship, endurance, and transformation. The story of Indo-Jamaicans is not only about migration — it’s about cultural collision, economic exploitation, survival, and integration into a Caribbean society trying to heal from the wounds of slavery.

Indenture After Emancipation: A Colonial Answer to Labor Needs

When Britain abolished slavery across its empire in the 1830s, plantation owners in Jamaica were desperate for cheap labor to keep the sugar economy afloat. Attempts to recruit Europeans failed. The former enslaved Africans, now freed, understandably demanded fair wages and better conditions — demands that planters resisted.

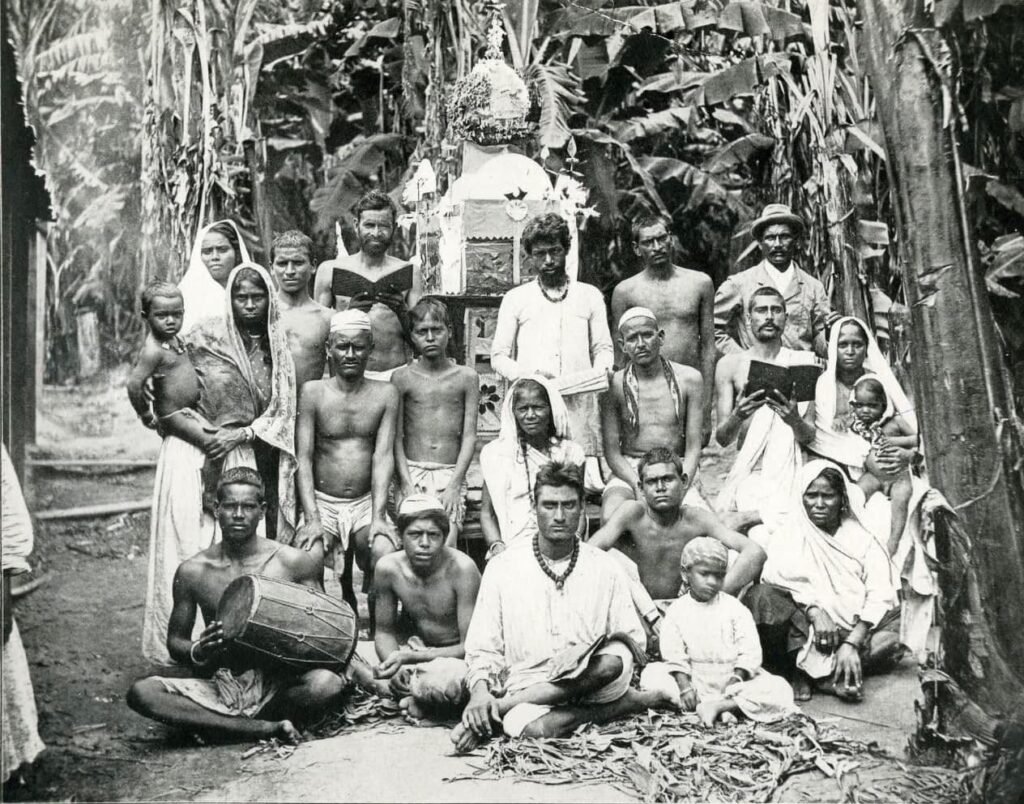

The solution came from thousands of miles away. Between 1845 and 1917, over 36,000 Indians were transported to Jamaica under the Indian indenture system, replacing forced labour with a deceptive contract system that often mimicked slavery in all but name. The very first group of Indians landed in Old Harbour Bay aboard the SS Blundell on May 10, 1845, a date now marked as Indian Arrival Day in Jamaica.

Primarily recruited from Bhojpur and Awadh in North India, and to a lesser extent from South India, these migrants came from regions plagued by famine, political instability, and British economic disruption. The promise was simple: five years of work in the Caribbean followed by return passage or settlement incentives. But the reality was far grimmer.

Coolie Wages, Colonial Disdain

Indians were lured with the hope of earning a “fortune” and returning to a better life in India, but the indenture system had exploitative roots. Unlike African-Jamaicans — who had just emerged from slavery — the Indian laborers were paid even less, and their contracts bound them to plantations with little room for freedom. Most were illiterate and could not read the English-language contracts, often signing with a thumbprint and little understanding of what awaited them.

A key insult was the label “coolie”, a derogatory term that stigmatized their low labour status and foreignness. This, coupled with cultural differences — from language and food to religion and clothing — resulted in tensions not only with the British authorities but also with the African-Jamaican population.

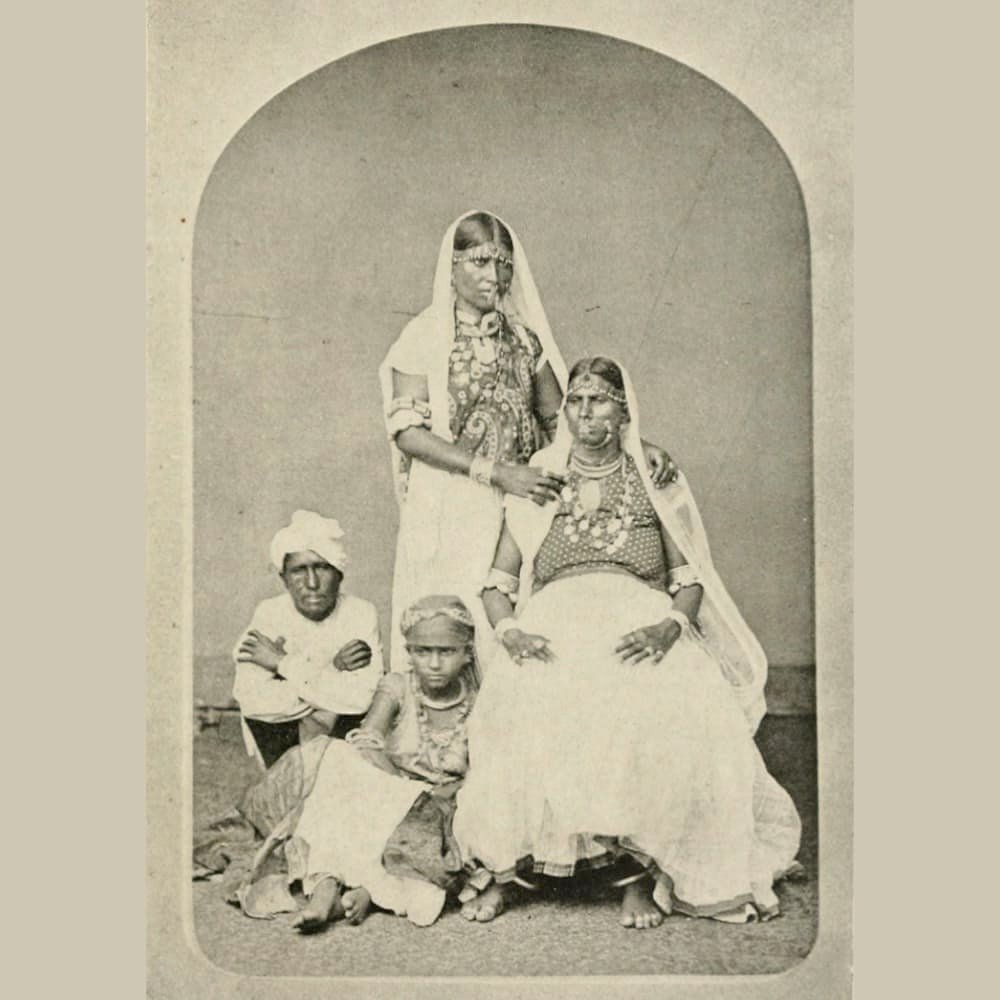

Living in the Margins: Women, Faith, and Identity

Perhaps one of the most tragic dimensions of the indentureship experience was the gender imbalance. Women made up a mere 11% of the Indian migrants between 1845 and 1847. This imbalance led to fierce competition among men for partners, sometimes resulting in wife murders and social unrest within Indian settlements. Indian women were often pursued by Chinese migrants due to the shortage of Chinese women, leading to the emergence of Chaina Raial (children of Chinese-African-Indian unions).

Religious life was an uphill battle. Hindu and Muslim Indians received little to no institutional support, and priests were not formally recruited. Many practicing clerics came as indentured laborers themselves and served as spiritual leaders part-time. Non-Christian marriages weren’t recognized until 1956, and over time, many Indians converted to Christianity or adopted Anglicized names as a strategy of survival and assimilation.

Staying or Leaving: The Repatriation Dilemma

While some Indians returned to India after completing their contracts, two-thirds remained in Jamaica, often not by choice. Repatriation was expensive and complicated. Ships would only sail if full, and when oversubscribed, many were left behind. World War I further disrupted travel, and many Indians who wished to return had lost touch with their homeland, culture, or kin.

The Jamaican government, keen to keep the labour force, offered small parcels of land (10–12 acres) or cash incentives for Indians to settle permanently. Gradually, many left the plantations and re-entered trades familiar to their ancestors: goldsmiths, barbers, fishermen, and shopkeepers.

Cultural Contributions: From Ganja to Goldsmiths

Although a small percentage of the population, Indo-Jamaicans have had an outsized impact on Jamaican society.

Ganja, now globally synonymous with Rastafarianism, was introduced by Indians, who traditionally used it in Hindu spiritual rituals. Its adaptation into Rastafari practices illustrates the deep cultural blending in Jamaica.

Cuisine is another enduring legacy. Dishes like curry goat, roti, dhal, chokha, tarkari, and pholourie have become staples of Jamaican street food, seamlessly blending with the nation’s culinary identity.

Jewellery-making, especially gold bangles and pure 18-karat craftsmanship, dates back to the 1860s, with Indian families like the Jadusinghs establishing some of the earliest shops in Kingston.

They also introduced plants and spices like tamarind, mango, jackfruit, betel nut, and coolie plum — all now naturalized parts of Jamaica’s ecosystem.

Despite early exclusion, Indo-Jamaicans now hold positions across all sectors, from politics to entertainment. Icons like Edward Seaga, former Prime Minister, and Toni-Ann Singh, Miss World 2019, highlight how Indo-Jamaican identity intersects with broader national pride.

Language, Names, and Erasure

As Indians assimilated into Jamaican society, many traditions were lost. The practice of naming children after gods, flowers, or seasons faded, replaced by English first and last names. Surnames like Singh, Maragh, Rampersad, and Beharry remain, but many others were Anglicized or lost.

Today, it is difficult to trace Indian lineage unless families intentionally preserved their heritage. In many cases, surnames are now the only visible link to the past — a quiet reminder of a once distinct identity now blended into the Jamaican whole.

Critical Reflections: Integration or Erasure?

While Indo-Jamaicans have largely integrated into society, we must ask — at what cost? The disappearance of traditional Indian languages, naming customs, spiritual practices, and caste structures (for better or worse) poses serious questions about cultural preservation vs. national unity. Was assimilation a form of liberation or a coerced forgetting?

And while some Indo-Jamaicans hold powerful positions today, the early experience was one of systematic exploitation, alienation, and discrimination. The indenture system, touted as a contract-based alternative to slavery, was still a mechanism of imperial control, racial hierarchy, and economic domination.

Legacy and Recognition

In 1995, Jamaica formally acknowledged this history by declaring May 10 as Indian Heritage Day. The National Council for Indian Culture in Jamaica, founded in 1998, continues to promote awareness and pride in Indo-Jamaican heritage.

This recognition, though overdue, is vital. It ensures that Jamaica’s rich multicultural identity doesn’t erase its constituent parts, but instead uplifts and celebrates them.

Conclusion: Many Threads, One Fabric

The Indo-Jamaican journey from indenture to integration is both a cautionary tale and a celebration. It is a story of trauma and triumph, of cultural dilution and dynamic fusion. While many Indians came chasing fortune, what they left behind was far greater — a legacy woven deep into the soul of Jamaica.

As the island continues to evolve, one truth remains: Jamaica is strongest when it honours all the roots that feed its tree — African, Indian, Chinese, European, and beyond. Only then does “Out of Many, One People” truly ring true.

Get Out of Many Faces, One People book here: https://a.co/d/cBzxiCU

I just want to say how much I enjoyed reading this—it was truly enlightening. As someone who is Ghanaian and recently discovered my Indo-Jamaican roots, I learned so much. I genuinely wish more people would educate themselves about the legacy and history of Indo-Jamaicans. It saddens me that so much of the culture, traditions, and historical narratives have been lost or overlooked.

Being American-born to Ghanaian parents, I’ve often struggled with my identity. I’d get long, curious stares or be stopped on the street by strangers asking, “Are you Black and Indian?” At times, I questioned myself because, while I have Afro features, I also have long, thick, black curly hair. Out of curiosity, I took an AncestryDNA test—and it confirmed what many had suspected. Interestingly, those who asked were rarely Africans; most were Caribbean especially Jamaican people who were familiar with Afro-Indian (Dougla) heritage and its history.

Though both of my parents are Ghanaian, I recently discovered that I have an Indo-Jamaican great-grandparent—an Afro-Indian Dougla—who migrated to Ghana during the Pan-Africanism movement of the 1950s, inspired by leaders like Kwame Nkrumah and Marcus Garvey. I believe my ancestor contributed to the rich Indo-Caribbean legacy of Jamaica and helped shape its diverse demographic landscape.

One day, I hope to share my story and DNA results more widely—to remind others that people like me do exist, and that we’re still proudly representing Jamaica, even from the other side of the world.