Long before Jamaica gained independence in 1962, freedom was already being carved into the island’s mountainous heart by self-liberated Africans who refused to bow to colonial chains. At the forefront of this fierce resistance stood Captain Cudjoe — a warrior, strategist, and the legendary leader of the Leeward Maroons. His legacy is one of defiance, diplomacy, and deep ancestral pride. Known also as Codjoe, Cudjo, or Kojo (an Akan name given to boys born on Monday), this Jamaican hero helped shape a unique chapter in Caribbean history — one written not by colonial rulers but by the blood, courage, and determination of a free African people.

From Enslavement to Sovereignty

Cudjoe’s exact origins remain partly wrapped in mystery, but the man who would become the most celebrated Maroon leader is believed to have been born around 1659. He was most likely descended from the Coromantee people of the Gold Coast (modern-day Ghana) and connected to the Sutton Estate rebellion of 1690 — one of the earliest large-scale revolts in Jamaica. Oral traditions from Accompong Town recount that he was the freeborn son of Naquan, a leader of that rebellion.

In the chaos of colonial conquest, as enslaved Africans sought refuge from the brutality of plantation life, many found sanctuary in the treacherous Cockpit Country. Here, surrounded by steep limestone hills and dense vegetation, they formed powerful communities — the Maroons — and resisted British domination for decades.

Rise of a Leader

In 1720, Cudjoe secured his position as leader of the Leeward Maroons by reportedly defeating a rival — a self-liberated African of Madagascan origin — in battle. From this point onward, he would command a network of warriors whose guerrilla warfare tactics humiliated British troops, year after year. Armed with superior knowledge of the terrain and an unyielding commitment to liberty, Cudjoe turned the mountainous stronghold of Cudjoe’s Town (later Trelawny Town) into an unconquerable fortress of Black sovereignty.

The Leeward Maroons under Cudjoe were one half of a larger Maroon resistance. The other was the Windward Maroons, led by the equally iconic Queen Nanny and her lieutenant Quao. Though separated by distance, both factions shared one unshakable vision: freedom at any cost.

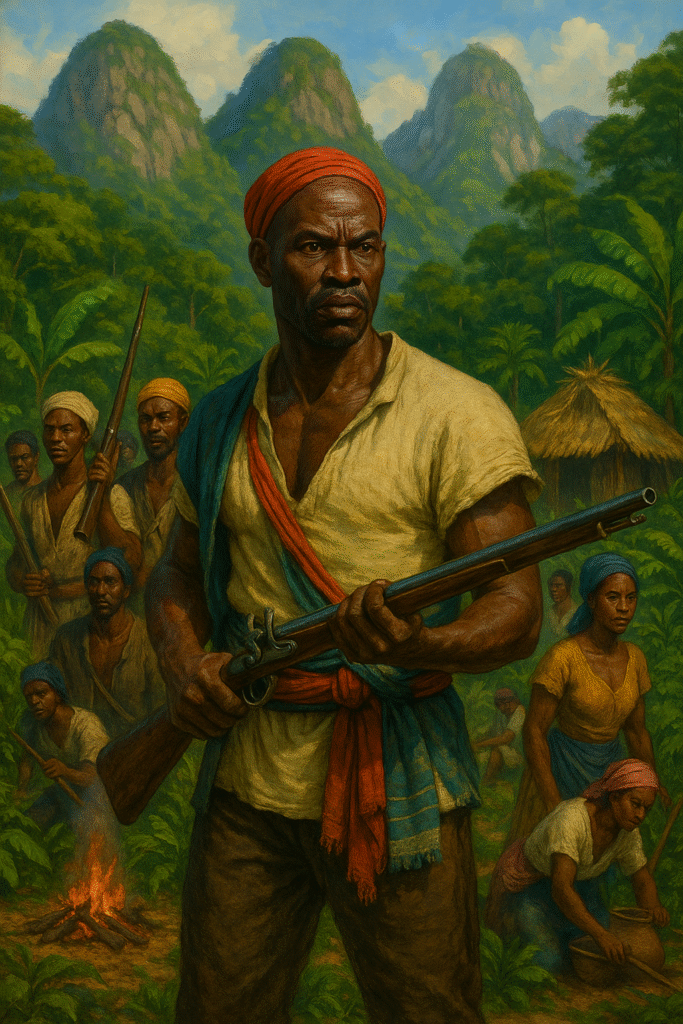

A Man of Fierce Presence

Descriptions of Cudjoe offer fascinating glimpses into his presence. While physician R.C. Dallas, writing long after Cudjoe’s time, painted him as a wild and stocky figure, it was the writings of infamous slaver Thomas Thistlewood that brought more vivid detail. In his 1750 diary, Thistlewood recalled seeing Cudjoe “with a feather’d hat, sword at his side, gun upon his shoulder… Bare foot and bare legg’d, somewhat a Majestic look.” This was not merely a warrior — he was a living symbol of resistance.

Peace Without Surrender

After years of war, British forces realized they could not conquer the Maroons. In 1739, they were forced to sit at the negotiation table with Cudjoe. The resulting treaty was historic. It recognized the Leeward Maroons as an autonomous people, granted them land, and exempted them from taxes. In return, Cudjoe agreed to stop sheltering newly escaped enslaved Africans and pledged to suppress future rebellions.

While controversial, the treaty marked a rare and remarkable moment: the British empire conceding defeat to a community of formerly enslaved Africans. But the cost was heavy — some Maroons viewed it as a betrayal, and even rebelled in the 1740s. Cudjoe swiftly quelled the dissent, asserting the necessity of peace after generations of war.

Final Years and Death

Though some accounts claim Cudjoe died just five years after the treaty, records from Edward Long and Thomas Thistlewood suggest he lived until at least 1764. That year, Governor William Lyttleton witnessed a martial display by the Maroons, led by none other than Cudjoe. Later that same year, Thistlewood recorded news of the leader’s death.

Cudjoe’s passing sparked a power struggle. Though the 1739 treaty named Accompong as his successor, the colonial governor undermined that authority, asserting more control over the Maroon communities. Still, Cudjoe’s legacy could not be buried — it had already been etched into the hills and valleys of Jamaica.

A Legacy That Echoes

Today, Cudjoe Day is celebrated in Jamaica on the first Monday of January — not just as a remembrance of a leader, but as a celebration of freedom, rebellion, and resilience. The town of Accompong in St. Elizabeth still upholds Maroon traditions, keeping alive the memory of Cudjoe and the ancestors who fought beside him.

Captain Cudjoe was more than a leader — he was a vision made flesh, a warrior-king who dared to challenge an empire and win. His story is a cornerstone of Jamaican identity and a bold reminder that freedom, once claimed, can never be forgotten.