Grace Jones is often summarized as “one of the first Black supermodels.” That shorthand misses the bigger truth: the Spanish Town–born artist helped redefine what a model, a pop star, and a screen presence could be—and she did it on the world stage while carrying unmistakably Jamaican confidence.

Roots and early years

Grace Beverly Jones was born in Spanish Town, St. Catherine, in 1948 and grew up in a strict Pentecostal household. She migrated to the United States in her early teens, settling in Syracuse, New York. There, her height, bone structure, and self-possession led her into modeling. By the late 1960s she signed with Wilhelmina in New York, but it was her move to Paris in the early 1970s that changed everything.

Breaking into a closed industry

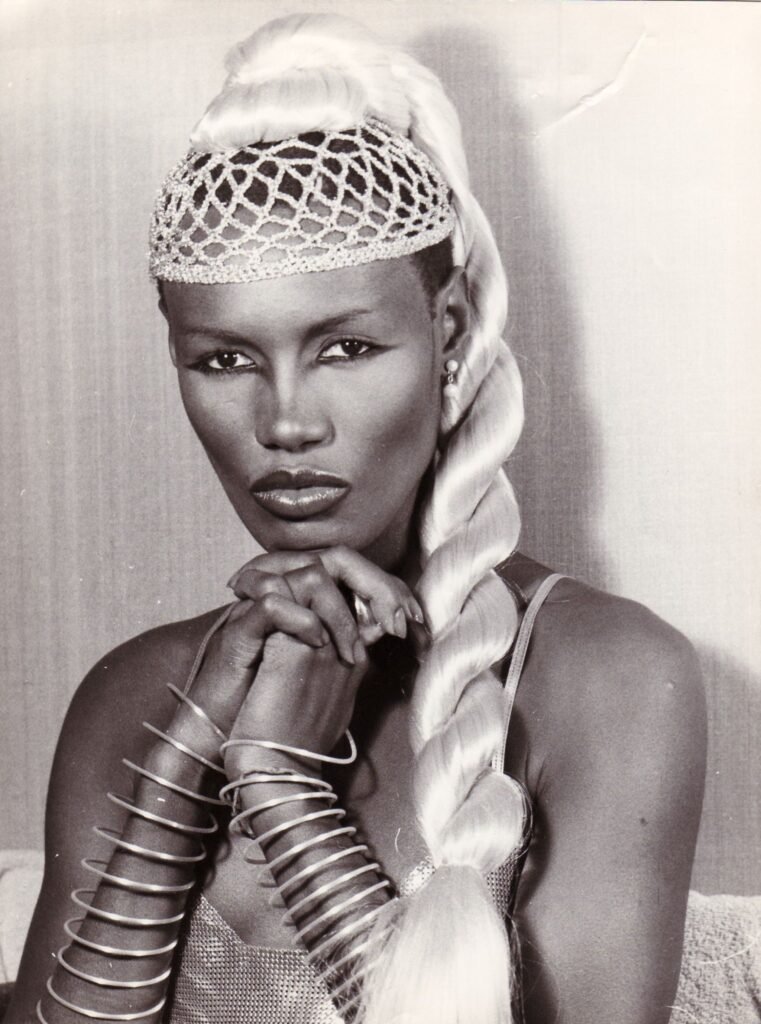

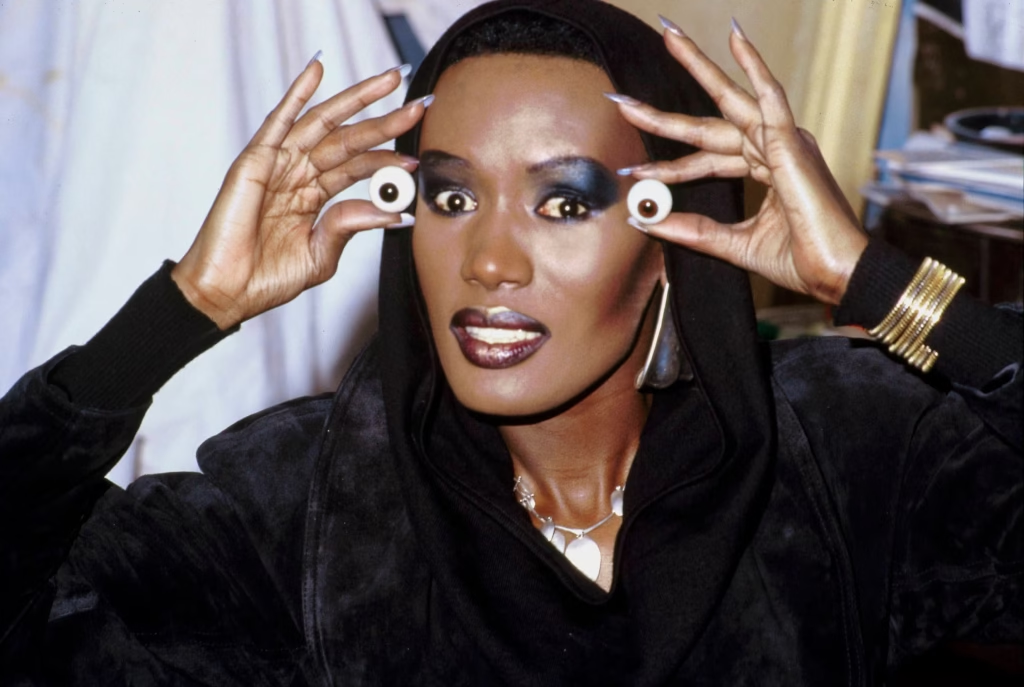

Fashion in the early ’70s was largely Eurocentric and white. A handful of pioneers—Donyale Luna, Naomi Sims, and later Beverly Johnson and Iman—had begun cracking doors open. Jones widened them. In Paris she walked for Yves Saint Laurent, Kenzo, and Azzedine Alaïa; shot editorials for Vogue and Elle; and became a fixture in the ateliers where silhouettes were invented, not just displayed. She did not try to soften her features or mimic existing norms. Instead, she turned angularity into aspiration, pairing a close-cropped fade with sculptural tailoring and a commanding gaze. The result was a new template for beauty: athletic, androgynous, unmistakably Black.

A visual revolution

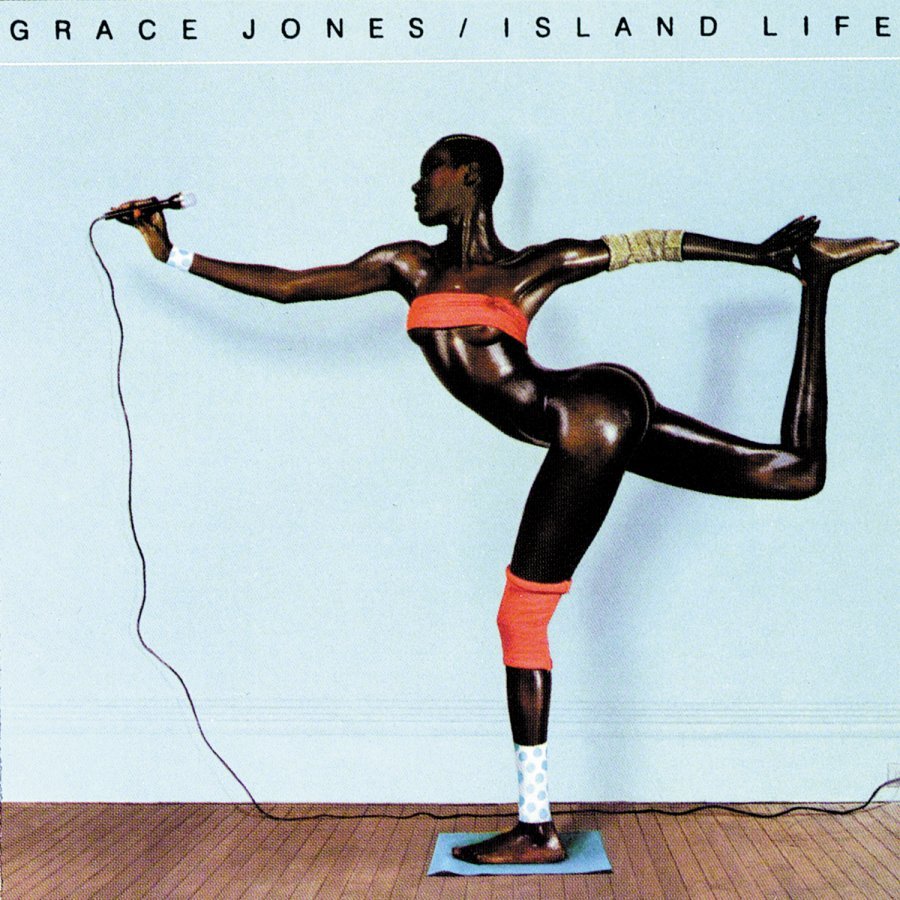

Jones understood image as strategy. In close collaboration with French photographer and art director Jean-Paul Goude, she built one of the most distinctive visual identities in popular culture—geometric hairlines, sharp suiting, and body-as-architecture poses that read instantly across a room or a record sleeve. Those images didn’t just decorate magazines; they challenged the fashion industry’s comfort zone and expanded casting horizons for future models and performers.

From the runway to the stage

While booking high-fashion work, Jones pivoted into music—first disco, then a sleek, genre-bending sound that fused reggae sensibility with new wave, funk, and rock. Albums like Warm Leatherette (1980), Nightclubbing (1981), and Slave to the Rhythm (1985) delivered enduring singles (“Pull Up to the Bumper,” “I’ve Seen That Face Before”) and turned her concerts into performance art. On stage she treated costume changes like sculpture, using Jamaican patter, patois, and dry wit to command audiences from London to New York. She wasn’t a model who sang; she was an auteur who used every medium available.

Film, television, and fearless presence

Hollywood took notice. As May Day in the James Bond film A View to a Kill (1985) and as Zula in Conan the Destroyer (1984), Jones delivered performances that were athletic, intimidating, and charismatic—roles that refused the narrow options usually given to Black women at the time. She also became a global television personality whose talk-show appearances—equal parts playful and confrontational—kept the culture guessing and watching.

Proudly Jamaican

Throughout, Jones foregrounded her Jamaican roots. She referenced yard style in her slang and swagger, kept a reggae pulse in band arrangements, and spoke openly about her upbringing. That cultural throughline mattered: it placed a Caribbean woman at the center of cutting-edge European fashion and American pop, proving that originality can come from an island of 4,240 square miles and reach every corner of the creative world.

What “first” really means

It is accurate—and important—to note that Jones was not the first Black model to break barriers. Donyale Luna appeared on British Vogue in 1966; Beverly Johnson graced American Vogue in 1974; Naomi Sims was a late-1960s trailblazer in advertising and editorial. Yet Jones belongs in the same pioneering cohort because of the scope of her impact: she brought avant-garde art direction, androgyny, and Caribbean cool into the mainstream simultaneously. She didn’t just appear in fashion; she changed fashion’s visual language and helped normalize non-Eurocentric beauty at the highest levels.

Lasting influence

You can see Jones’s fingerprints on decades of music videos, runway casting, editorial styling, and stagecraft. Designers reference her silhouette. Pop stars borrow her theatricality. Models benefit from the space she carved out for unconventional beauty—space that allowed later icons like Naomi Campbell, Alek Wek, and Adut Akech to thrive while looking wholly themselves.

Why this story matters now

When a social post declares, “One of the world’s first Black supermodels was Jamaican,” it’s pointing to something bigger than a trivia fact. It’s a reminder that representation often advances through audacity. Grace Jones’s career shows how a single artist can push multiple industries forward: modeling by reimagining beauty, music by merging genres and performance art, film by demanding presence, and culture by insisting that a Jamaican woman could be the standard, not the exception.

Bottom line: Grace Jones isn’t just a pioneering Black supermodel from Jamaica. She is a Caribbean-born architect of modern style and spectacle—an artist whose originality forced fashion, music, and film to expand their definitions of beauty and power.

international cannabis delivery available with blockchain tracking

Hi, how have you been lately?