Jamaica’s African heritage is not accidental—it is the result of centuries of calculated, systemic exploitation known as the transatlantic slave trade. This wasn’t a tragedy that “just happened.” It was a deliberate global enterprise, engineered by powerful economic and political forces, and supported by local African collaborators, European elites, and colonial administrators alike.

To understand why enslaved Africans were brought to Jamaica and who allowed it to happen, we must pull back the curtain on a vast, brutal machinery that turned human lives into currency, empires into superpowers, and Africa into a bleeding continent.

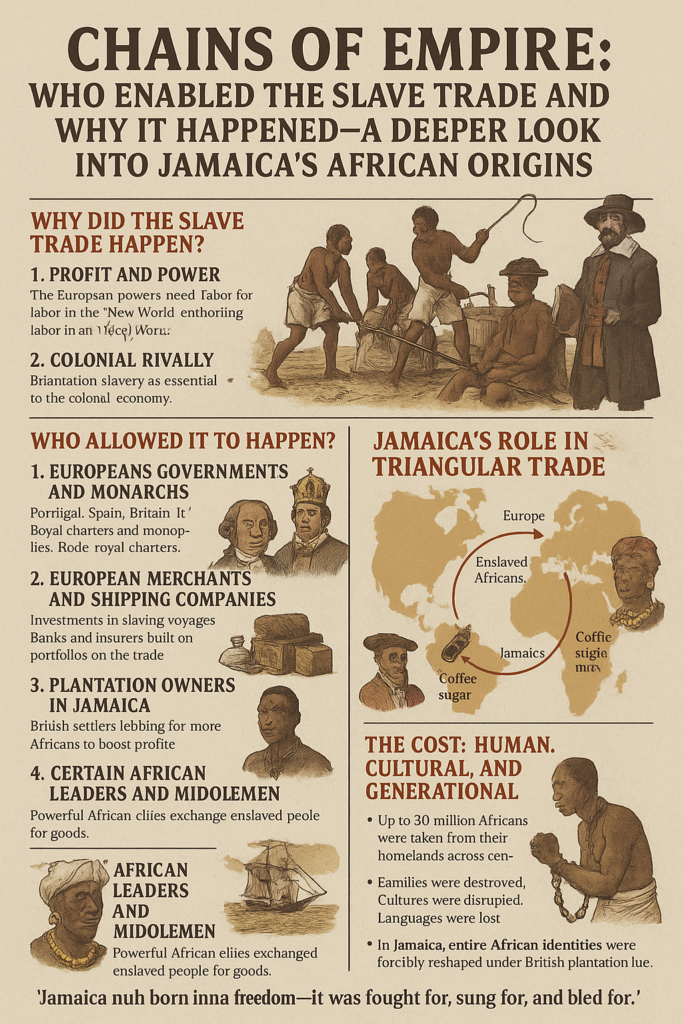

WHY DID THE SLAVE TRADE HAPPEN?

1. Profit and Power

At its core, the slave trade was about money. The European powers—Britain, Spain, Portugal, France, the Netherlands—were racing to build global empires and needed labor to exploit the so-called “New World.”

Jamaica, rich in fertile land ideal for sugarcane, became a colonial goldmine. But sugar cultivation was brutal, labor-intensive, and deadly. European indentured servants couldn’t survive the tropical climate and harsh working conditions. Africans, by racist colonial logic, were seen as more “suited” to endure such conditions. They were not considered people—they were “property,” and more slaves meant more profit.

This is why the transatlantic trade flourished: a human economy was created to fuel European wealth. Enslaved Africans were used to:

- Plant and harvest sugar, coffee, cotton, and cocoa.

- Build roads, plantations, and ports.

- Serve as domestic workers and skilled laborers.

2. European Demand

As sugar, tobacco, and rum became staples in Europe, demand skyrocketed. That demand made plantation slavery not just viable but essential to the colonial economy. European families enriched themselves sipping sweetened tea while Caribbean Africans died in cane fields.

3. Colonial Rivalry

The transatlantic slave trade was also a geopolitical strategy. Colonies like Jamaica weren’t just agricultural outposts—they were military and commercial assets. European nations fought wars and signed treaties over these islands. More slaves meant more production, which meant more wealth, which meant more dominance over rivals.

4. Religious Justification and Racism

European Christian monarchies wrapped their economic greed in religious robes. They claimed they were “civilizing” Africans, saving their souls from paganism. This moral façade helped justify a trade that was, in reality, inhumane and genocidal. Racist ideologies about African inferiority were developed and spread to ease the conscience of slave owners and European citizens.

WHO ALLOWED IT TO HAPPEN?

1. European Governments and Monarchs

- Portugal was the first European nation to formalize the Atlantic slave trade, establishing forts along the African coast as early as the 15th century.

- Spain, Britain, France, and others soon followed.

- The British government, through royal charters and monopolies like the Royal African Company, gave legal protection and infrastructure to slave traders.

- Queen Elizabeth I of England backed early slaving expeditions, including those of John Hawkins in the 1560s.

These governments not only allowed slavery—they profited from it through taxes, customs duties, and military protection of trade routes.

2. European Merchants and Shipping Companies

The slave trade was highly organized. Merchants invested in slaving voyages like modern investors buy stocks. Shipping companies insured slaves as “cargo.” Banks and insurance companies in London, Amsterdam, and Lisbon built entire portfolios on the slave trade.

3. Plantation Owners in Jamaica

British settlers and absentee landowners in Jamaica lobbied for more enslaved Africans to boost profits. They wrote letters to London demanding ships full of human cargo. Many of these men became wealthy aristocrats in Britain, shaping the country’s elite with blood money.

4. Certain African Leaders and Middlemen

This is perhaps the most difficult part of the story—but it must be told.

Some African kingdoms and merchants participated in the trade by capturing and selling rival ethnic groups to European traders. These were often prisoners of war or victims of raids. The demand from Europeans incentivized a system of internal African warfare and raiding. In many regions, powerful African elites exchanged enslaved people for guns, textiles, alcohol, and other goods.

- In places like the Gold Coast (now Ghana), Dahomey (Benin), and the Kongo Kingdom, local rulers sometimes grew rich from the trade.

- However, not all African societies participated. Some resisted, others collapsed under the pressures of slave raiding and warfare.

As historian John Thornton stated: “Europeans tapped into an already existing slave system in Africa but scaled it into an international enterprise.”

Yet as scholar Anne Bailey argues: “To say Africans were ‘partners’ in the slave trade is misleading. They had no power over European shipping, insurance companies, or the plantations where their people were sent. Their role was reactive—shaped by the violence and greed of foreign empires.”

A Mosaic of African Nations

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, nearly 600,000 Africans were transported to Jamaica, making it one of the largest recipients of enslaved Africans in the Caribbean. These were not a monolithic group. They hailed from powerful and diverse ethnic nations across the African continent—each with their own languages, governance, religious beliefs, and cultural practices.

Prominent among them were:

- The Akan (often referred to by the British as “Coromantee”), especially from the Asante, Bono, Wassa, Nzema, and Ahanta peoples of present-day Ghana.

- The Kongo people, from modern-day Congo and Angola.

- The Yoruba and Ibibio, from what is now Nigeria.

- The Fon and Ewe, from present-day Benin and Togo.

- The Igbo, whose numbers were vast and who left a lasting cultural imprint on Jamaican spirituality and resistance traditions.

The British colonizers often expressed a preference for the Akan, viewing them as disciplined and physically strong. But with that “strength” came defiance. The Coromantee were notorious for orchestrating rebellions and escaping plantations to form Maroon communities. This resistance forced slave traders to diversify their human cargo—intentionally breaking up ethnic solidarity to discourage uprising.

JAMAICA’S ROLE IN THE TRIANGULAR TRADE

Jamaica became a jewel in Britain’s empire, but its shine was stained with blood. It was a major hub in the triangular trade:

- Europe shipped manufactured goods to Africa.

- Africans were enslaved and shipped via the Middle Passage to Jamaica.

- Sugar, rum, and other colonial goods were shipped back to Europe.

Jamaica’s ports—Kingston, Montego Bay, Spanish Town—became arteries of this dark system. Slave markets, wharves, sugar plantations, and merchant houses formed the infrastructure of exploitation.

A SYSTEM BUILT ON SILENCE

For centuries, the world remained largely silent about the atrocities of slavery. Why?

- European nations denied or downplayed the cruelty.

- Slaveholders wrote the histories, often portraying Africans as lazy, uncivilized, or incapable of self-rule.

- Jamaican colonial law prohibited enslaved Africans from learning to read or write, ensuring that their stories were not recorded.

This silence protected wealth, white supremacy, and colonial rule. It also robbed generations of Jamaicans of the full knowledge of their ancestral greatness.

THE COST: HUMAN, CULTURAL, AND GENERATIONAL

- Up to 20 million Africans were taken from their homelands across centuries. Some estimates place the number higher when accounting for deaths during capture and transit.

- Families were destroyed. Cultures were disrupted. Languages were lost.

- In Jamaica, entire African identities were forcibly reshaped under British plantation rule.

And yet—through pain, Africans in Jamaica reconstructed themselves. They forged new identities, preserved fragments of their heritage, and resisted erasure.

CONCLUSION: NEVER BY ACCIDENT, ALWAYS BY DESIGN

The African presence in Jamaica was not an accident of history. It was the result of calculated political, economic, and racial systems engineered by empires and fueled by greed.

It happened because kings, queens, and businessmen allowed it—because African collaborators were seduced by guns and gold—because the world turned its head away.

But the people they enslaved did not forget.

Today, the spirit of those Africans lives on in every drumbeat, every proverb, every Maroon settlement, every Rastafari chant, every patois word, and every Jamaican who walks tall knowing that their ancestors were not victims—they were survivors.

“Jamaica nuh born inna freedom—it was fought for, sung for, and bled for.”

We remember not just that slavery happened—but who allowed it, why it thrived, and how those who endured it turned oppression into cultural greatness.

Real facts 💯