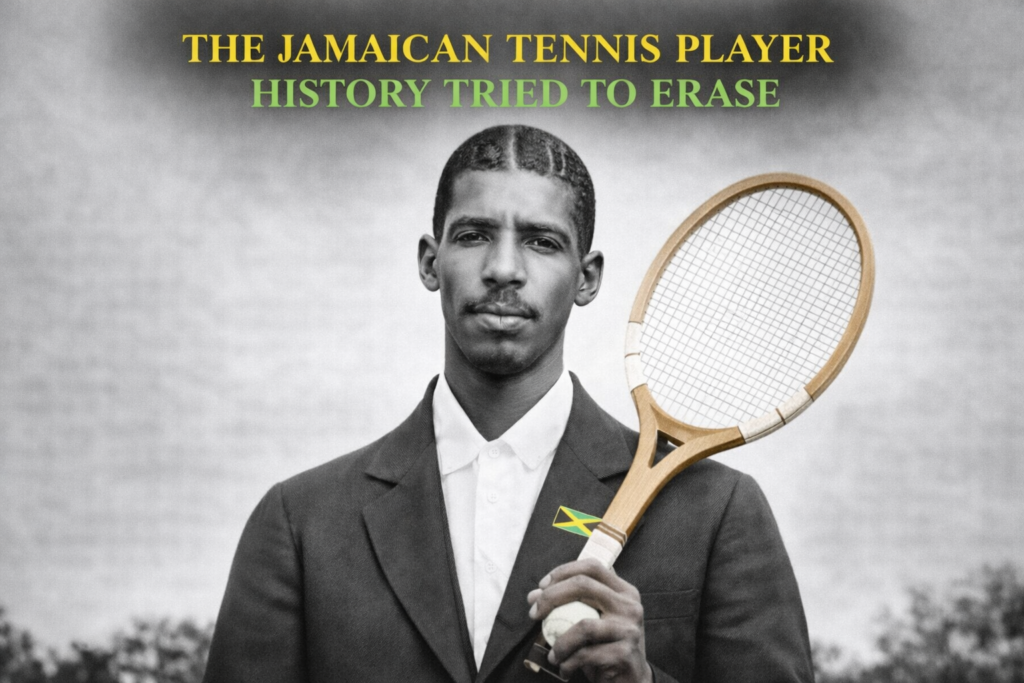

Long before global audiences associated Black excellence at Wimbledon with Arthur Ashe or Althea Gibson, a Jamaican quietly rewrote sporting history. His name was Bertrand Milbourne Clark—a civil servant by profession, a sporting polymath by passion, and the first Black person ever to compete at the Wimbledon Championships.

Born on 29 April 1894 in Kingston, Jamaica, Clark emerged from a family rooted in education and professional life. His father, Enos Edgar Clark, was a dentist, and the family belonged to a small but influential Black middle class navigating opportunity and restriction within colonial Jamaica. Educated at Kingston High School and later Jamaica College, Clark’s athletic talent surfaced early. In 1910, while still a student, he won the high jump at the very first Inter-Secondary Schools Championship Sports at Sabina Park, signaling the breadth of ability that would define his life.

A Rare Sporting Polymath

Clark was not confined to a single discipline. At a time when specialization was rare but resources for Black athletes were rarer still, he excelled across sports—tennis, cricket, golf, athletics, and even football. His versatility earned him respect in Jamaica as an all-round sportsman of exceptional caliber.

In cricket, he played for the prestigious Melbourne Cricket Club alongside his brother Ronald, earning praise for his elegant cover drive. In golf, he rose to become one of Jamaica’s leading players and later served as Secretary of the Jamaica Golf Association from 1941 to 1951, shaping the sport administratively as well as competitively. His influence extended beyond the field: he wrote extensively on cricket, tennis, and golf, gaining a reputation as one of the Caribbean’s finest sports writers.

Dominance on the Tennis Court

It was in tennis, however, that Clark’s dominance was most visible. He became the All-Jamaica singles champion for seven consecutive years, an extraordinary feat that cemented his place at the top of the island’s tennis hierarchy. Across Jamaica’s national championships, he accumulated nineteen titles: seven singles, seven doubles, and five mixed doubles—numbers that remained unmatched for decades.

His talent carried him beyond the Caribbean. In 1920, Clark defeated American Tally Holmes to win the American Tennis Association title, then the premier championship for Black players in the United States. This victory established him as one of the leading Black tennis players in the world at a time when racial barriers excluded most from mainstream international competition.

Wimbledon, 1924: A Quiet Revolution

In 1924, Clark entered the Wimbledon Championships, becoming the first Black person to ever compete at the tournament. There were no ceremonial acknowledgments, no headlines celebrating the moment. He lost in the first round to Britain’s Vincent Burr, but the result mattered far less than his presence. On the manicured lawns of the All England Club—an institution emblematic of British social hierarchy—Clark stood as a visible challenge to exclusionary norms.

He returned to Wimbledon in 1930, again competing in the men’s singles. That two appearances passed largely unnoticed by history speaks less to his significance and more to how quietly barriers could be broken when those doing the breaking were not meant to be remembered.

An Unusual Symbol of Equality

One of the most striking episodes of Clark’s life occurred in 1927 during a royal visit to Jamaica. Prince Albert, Duke of York—later King George VI—was an avid tennis player and arranged a doubles match during his stay. Clark, as Jamaica’s champion, was invited and partnered directly with the prince. In an era rigidly structured by race and class, a Black Jamaican playing as an equal alongside British royalty was almost unheard of. Contemporary observers viewed the match as a subtle but powerful display of racial equality.

Life Beyond Sport

Despite his international sporting achievements, Clark never turned professional. From 1911 onward, he worked in Jamaica’s civil service, beginning as a Treasury clerk and eventually retiring as secretary of the Island Medical Office. He balanced global competition with public service, traveling extensively—often first class—yet returning to his duties without fanfare.

He was twice married, had no children, and lived a life marked more by discipline than spectacle. His name appeared in the 1946 edition of Jamaican Who’s Who, reflecting the respect he commanded locally, even as international recognition eluded him.

Death, Obscurity, and Rediscovery

Bertrand Milbourne Clark died on 30 March 1958 at the age of 63. His obituary in the Sunday Gleaner described him as “perhaps the greatest all-round Jamaican sportsman of our time.” For decades, that praise remained largely confined to Jamaica.

It was not until 2019 that his global significance resurfaced. Research by Wimbledon’s library and family genealogists confirmed what history had overlooked: Clark, not later legends, was the first Black competitor at Wimbledon. The discovery corrected a long-standing omission and repositioned Jamaica at the very beginning of Black tennis history on the world’s most exclusive stage.

A Legacy Finally Seen

Bertrand Milbourne Clark did not protest, posture, or seek acclaim. He competed, excelled, and moved on—allowing his performance to speak in spaces that were never designed to hear it. His legacy lies not only in being first, but in demonstrating that excellence could exist quietly, even under the weight of colonial and racial barriers.

Today, his story stands as both a correction and a reminder: history often remembers the loudest breakthroughs, but it is built just as much by those who broke barriers in silence.